Photographing Crocodiles and Cenotes in Quintana Roo: A Travel & Photo Guide

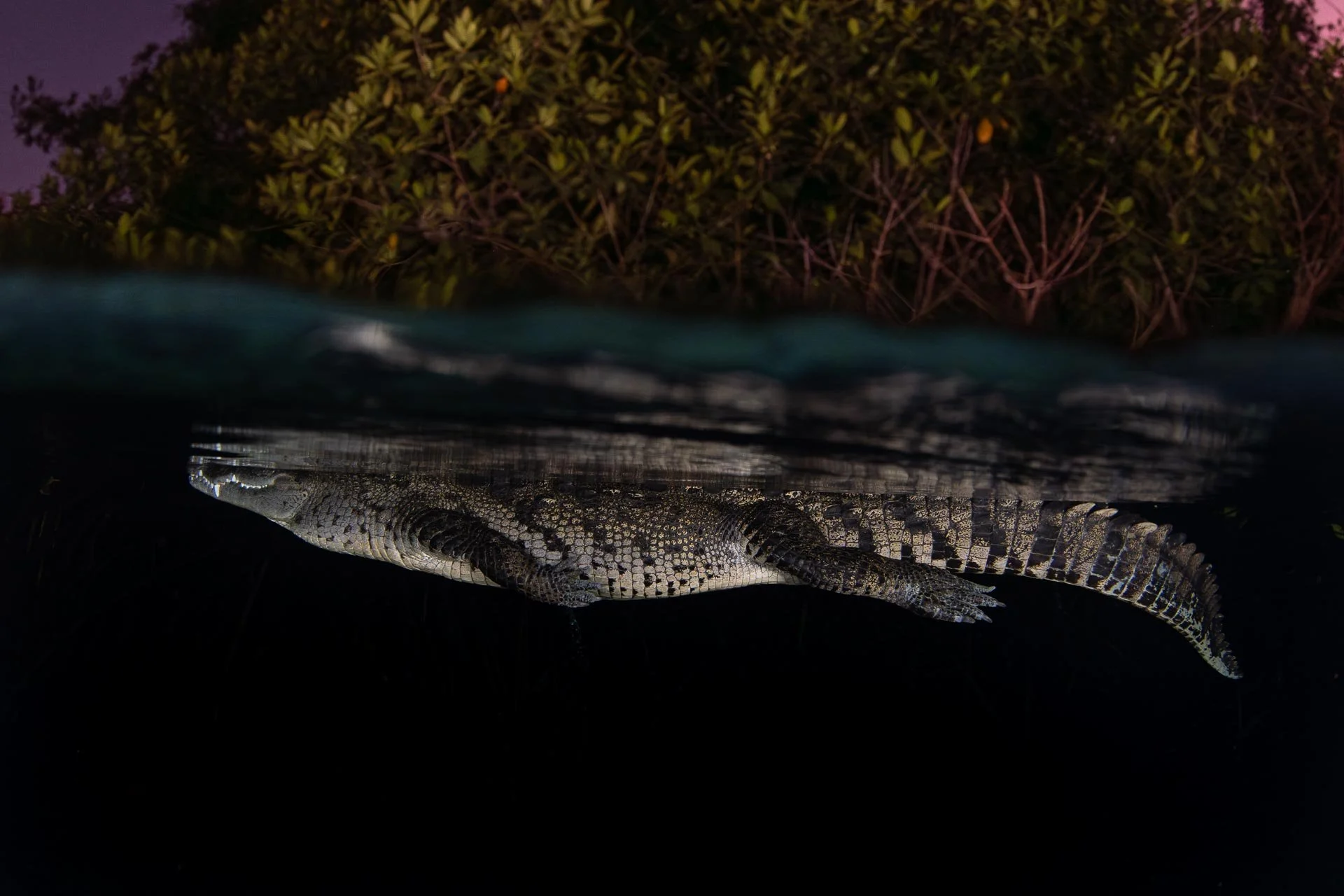

Stillness beneath the surface — a Morelet’s crocodile in its hidden realm.

We had been to Mexico before, but never to this side of the Yucatán Peninsula, and I had always wanted to explore the famous cenotes around Tulum.

These freshwater sinkholes are iconic for travelers and a dream for underwater photographers - but one cenote in particular had been on my mind for some time. It’s home to a resident Morelet’s crocodile, a local character known for his unusual tolerance of nearby divers and snorkelers.

Lately, I’ve become increasingly fascinated with observing and photographing crocodilians in their natural environment. That curiosity led me from the mangroves of Cuba’s Jardines de la Reina to the shallow forests of Indonesia, always hoping for a meaningful encounter.

Since Banco Chinchorro - Mexico’s most well-known croc habitat - is off the table for whatever unfortunate reasons, hearing about this individual Morelet’s crocodile felt like an opportunity I couldn’t ignore.

What Are Cenotes? And Why Mangrove Cenotes Are So Unique

Cenotes are natural freshwater sinkholes found throughout the Yucatán Peninsula, formed when limestone bedrock collapses and reveals the underground rivers flowing beneath.

These openings connect to one of the largest subterranean water systems on Earth - a vast network of flooded caves and tunnels shaped over millions of years. Most cenotes are deep, enclosed chambers with crystal-clear water and striking light rays.

But along the Caribbean coastline, a few cenotes are different.

Instead of being closed caverns, these cenotes form long, open channels bordered by dense mangrove forests. Their proximity to the sea allows saltwater to seep in through hidden underwater passages, creating a rare blend of freshwater and marine influence. Sunlight pours directly into the water, and mangrove roots twist down into the cenote, creating a complex maze of shelter and shade.

Because of their open structure and thriving mangrove habitat, these coastal cenotes often support far more visible wildlife than the darker, cavern-type cenotes found elsewhere in the region. The mangroves act as nurseries and filters, stabilizing the water and providing endless hiding places for a surprising variety of creatures.

This unusual combination of geology and mangrove forest creates a cenote ecosystem unlike any other on the peninsula.

Night Photography With a Crocodile

We had planned our main crocodile photography attempts for after sunset, teaming up with a local photographer who knew the area well.

Like many reptiles, crocodiles become more active at night - and they have a few tools that help them do so:

Their vision is adapted for low-light hunting

The lower temperature at night helps them regulate their temperature, meaning they can move around and feed more efficiently

During daylight hours, you’ll often see them soaking in the sunlight and storing up energy.

Getting To Grips With The Cenotes

But before heading out for any night work, we decided to ease into the environment with a scuba dive the very next morning after we arrived. Cenote diving can be tricky, so we wanted to get used to the environment first before challenging ourselves with a night dive.

We explored two local cenotes, getting a feel for the water, the visibility, and the layout of the mangrove channels.

To our luck, we even spotted the crocodile during the day, resting exactly where locals said he might be - perched on his usual sunning spot about halfway along one of the cenotes.

Relaxed and sun-warmed, the cenote’s quiet sentinel.

Seeing the crocodile up close - relaxed, sun-warmed, and completely at home - set the tone for the days ahead.

Night would bring a very different mood, but this first encounter reminded me that even in a place as serene as a cenote, the wildlife is always quietly watching.

Understanding the Crocodile’s Behavior

Morelet’s crocodiles are typically shy, solitary reptiles found in freshwater habitats across Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala.

They prefer calm lagoons, mangrove forests, and slow-moving rivers - places where they can remain partially hidden while regulating their body temperature. Although they are apex predators, they are also cautious by nature and tend to avoid unnecessary confrontations.

This particular crocodile has lived in the same stretch of mangrove-fringed cenote for years, making it very much his territory. Because he sees snorkelers, divers, and locals on a regular basis, he has become unusually tolerant of human presence. He doesn’t associate people with food, and the ecosystem gives him more than enough space to retreat when he chooses, which likely plays a role in his calm behavior.

“Friendly” isn’t quite the right word - he is wild, after all - but his relaxed, predictable demeanor is a sign of an animal accustomed to sharing his habitat without feeling threatened.

Gaping, a natural posture often observed during periods of rest.

Ethics and Safety When Photographing Wild Crocodiles

The most important thing to think about when photographing wild crocodiles is being respectful.

You should never interfere with their natural behavior, which means no baiting or blocking movement, including blocking retreat angles.

It is also critical to avoid associating humans with food or reward. This individual’s tolerance likely comes from years of neutral encounters, not conditioning. Preserving that balance protects both people and the animal.

The First Night Attempt

Seeing the crocodile earlier during the day gave us the confidence to make our first dive attempt on the same evening, rather than waiting any longer.

We entered the water just before sunset, hoping to find him settled among the mangroves.

And we did - tucked between the roots, watching us quietly. But the bubbles from our scuba regulators eventually spooked him. Crocodiles are extremely sensitive to vibrations, and the noise of exhaled bubbles carries far through the still water. After a short while, he slipped deeper into the roots and vanished.

The crocodile moving through the mangroves shortly after sunset.

This quickly made us realize how challenging this would be, and that our approach needed to change if we wanted a chance to get the photographs.

Back After Sunset - This Time on Snorkel

A few days later, we returned after sunset with a local photographer who knew the crocodile’s nocturnal habits well.

This time, we left the scuba gear behind and slipped into the water with only snorkels. Without bubbles, without tanks, and without the mechanical hiss of regulators, the cenote felt completely silent - and far less intrusive for the crocodile.

We found him near the entrance, floating just below the surface, perfectly motionless. He didn’t seem to mind us at all. No hissing, no sudden movements, no signs of stress or aggression.

A motionless crocodile just beneath the surface, mirrored by the water above.

Just quiet observation.

Most of the time, he appeared like a statue carved out of deep time.

But his calm behavior shouldn’t be taken for granted. He is still an apex predator, fully capable of explosive power when he chooses. Even while he held still, I could feel him watching us - slow, deliberate, and aware of every ripple we made.

We kept a respectful distance, moved slowly, and avoided blocking his path or making sudden gestures. Within those boundaries, we were able to spend some time photographing him: using backlighting to shape the scene, taking close-up portraits, and trying to capture the quiet patience in his eyes.

Second Round

By the next weekend, we had a better sense of his rhythm.

During the day, he preferred to rest on his usual sunning spot, but just before sundown, he would begin his slow journey toward the cenote entrance. If we timed it right, we could catch him “in the act,” gliding through the mangroves in that magical hour where daylight fades, and the sky turns purple.

So we planned to return a little earlier that evening, hoping to follow his movement and try something different - split shots, capturing both the mangrove canopy above and the crocodile below in a single frame.

The conditions would be challenging, but the idea of photographing him in transition, half in daylight and half in darkness, felt too good to pass up.

A Smaller Encounter in the Mangroves

Not every moment in the cenote revolved around the crocodile.

During one of our night dives, I spotted a blue crab (Cardisoma guanhumi) on the bottom, firmly holding a nearly transparent shrimp it had just captured.

After sunset, the cenote transforms - shrimps emerge from hiding, fish begin to hunt, and blue crabs patrol the substrate in search of food.

Observed at night, a blue crab holding its prey on the cenote bottom.

Photo Tips for Cenotes and Low-Light Wildlife

Photographing in a mangrove cenote is unlike shooting in the open ocean, and requires specialist knowledge.

Light, particles, haloclines, and wildlife behavior all create their own challenges. Here are a few practical tips based on what worked for me.

1. Start With Natural Light

Mangrove cenotes have soft, uneven lighting. I often begin with natural light and only raise ISO when needed.

Angling yourself so the subject is lit by open sky creates more flattering, atmospheric shots than blasting everything with strobes.

2. Use Strobes Sparingly

Strobes can bring out detail, but in these environments, they also highlight particles and risk disturbing wildlife. At night, I relied mostly on backlighting to add shape without overwhelming the scene.

3. Move Slowly

Sediment, roots, and still water mean any sudden movement creates clouds or vibrations. Smooth, controlled motion results in cleaner images and calmer wildlife - especially crocodiles.

4. Position Yourself Smartly

For crocodiles: stay low, stay calm, and never block their path. Eye-level angles work best, and small adjustments are better than big maneuvers.

Their body language tells you immediately if they’re uncomfortable.

5. Split-Shot Technique (Over-Unders with a Moving Subject)

Split shots in cenotes are challenging even when nothing moves - but when your subject is a crocodile that never stops swimming, the difficulty increases tenfold.

As the croc made his slow journey toward the entrance, I had to move with him. My approach was simple but effective:

I would stop for a moment, stabilize the dome, use back-button focus, and wait for him to swim into the frame on his own.

As soon as he entered the composition, I fired a short burst of frames, then slowly swam ahead of him again to reset.

I repeated this over and over, for several minutes, until we reached the entrance.

There were a few things that really helped out here:

Use a large dome port to get cleaner transitions between above and below.

Shoot during golden hour for balanced topside exposure.

Hold the dome steady - even tiny ripples distort the split line.

Move slowly and deliberately, staying slightly ahead without blocking his path.

Let the crocodile enter your frame, rather than chasing the shot.

When the timing works - still water, soft light, and a crocodile gliding through mangrove roots - the results can feel surreal: half jungle, half prehistoric reptile, all in one frame.

6. Mind the Water Column

Mangrove cenotes often have haloclines and suspended particles. Staying slightly above the halocline and avoiding the bottom keeps your images crisp.

7. Use Wide Angle

A fisheye or wide-angle lens lets you get close - reducing particles - while still showing the roots, channel, and the animal in its environment.

8. Prioritize Safety

Even the calmest crocodile is still an apex predator. Maintain distance, avoid blocking escape routes, and let the animal decide how close the encounter becomes.

Final Thoughts

Mangrove cenotes are fragile ecosystems - windows into a world shaped by roots, freshwater, and time.

Encounters with wildlife here, especially apex predators like Morelet’s crocodiles, are a privilege. Working slowly and respectfully allowed me to witness behavior that feels almost prehistoric, and it reminded me just how important it is to protect these habitats.

If you decide to explore cenotes, travel gently. Support operators who value conservation, avoid disturbing wildlife, and remember that the best photographs come from patience, not pressure.

These ecosystems deserve to stay wild - for the wildlife that depends on them, and for the rare moments they offer to those who visit.